The text below is an article published in the danish newspaper Politiken in 2006.

Rådhuspladsen er et af de helt centrale mødesteder i byen. Det er her, man fejrer landsholdet, tænder juletræet og demonstrerer mod krig eller nedskæringer i børnehaverne.

Ud over at være et fysisk rum, der kan diskuteres ud fra smag og behag, har denne plads i byen en central demokratisk funktion som et sted, der helt konkret lægger rum til byens mangfoldighed. Med planerne om en ny metropolzone i København er der lagt op til diskussion om Rådhuspladsens udseende igen. Og netop fordi pladsen har så vigtig en funktion for demokratiet i byen, burde denne diskussion være et forbillede for, hvordan meninger kan brydes og alligevel føre til en konstruktiv proces, der ender med forslag til en plads, der ikke findes mage til i hele verden. Noget kunne tyde på, at diskussionen tager en anden drejning.

Politikens leder ‘Storbydrømme’ fra sidste lørdag skriver om, at det skal være slut med kværulantisk brok, der bremser arkitekternes ambitioner, som det f.eks. var tilfældet med Krøyers Plads på Christianshavn. København skal ifølge lederen være en såkaldt ‘Kreativ Monopol (sic!) – med fokus på Teknologi, Talent og Tolerance’. Der skulle naturligvis have stået ‘Metropol’, men skrivefejlen kunne minde om den slags fortalelser, der ikke er helt tilfældige. Lederen overser bl.a., at medierne også spiller en rolle i forhold til, hvordan folk udtrykker deres mening og agerer i det ‘offentlige rum’. Eksemplet med Krøyers Plads viser, at det var først, da debatten blev til den kedelige sort-hvide brok, at medierne for alvor begyndte at dække sagen – eller var det først, da medierne trådte ind, at debatten blev sort-hvid? Hvorom alt er, så belønnede medierne dem, der stod stejlt.

Krøyers Plads er desværre et eksempel på, hvordan et kæmpe potentiale i form af en masse engagerede mennesker, et visionært projekt og byens populæreste strandbar bliver spildt i en ukonstruktiv debat eller byudviklingsproces, der endte med at sætte alle parterne i hver sin bås. Enten får de rollen som brokkehoveder med højdeskræk eller rollen som visionære arkitekter med det ‘kreative monopol’.

I byudviklingslaboratoriet Supertanker arbejdede vi med at bryde disse fastlåste mønstre ved at gøre mødet mellem byens parter mere urbant gennem åbenhed og jævnbyrdighed. Vi brugte en lang række metoder til bl.a. at gøre de borgeres ønsker mere konkrete og konstruktive. Vi var i høj grad inspireret af, hvordan Havneparken på Islands Brygge var blevet til i et sådant konstruktivt samspil mellem de lokale byboere og Københavns Kommune. Vi oplevede, at det var muligt at bryde disse ukonstruktive mønstre, men at de grøfter, der allerede var gravet på Krøyers Plads, var for dybe, til at der kunne bygges bro mellem parterne.

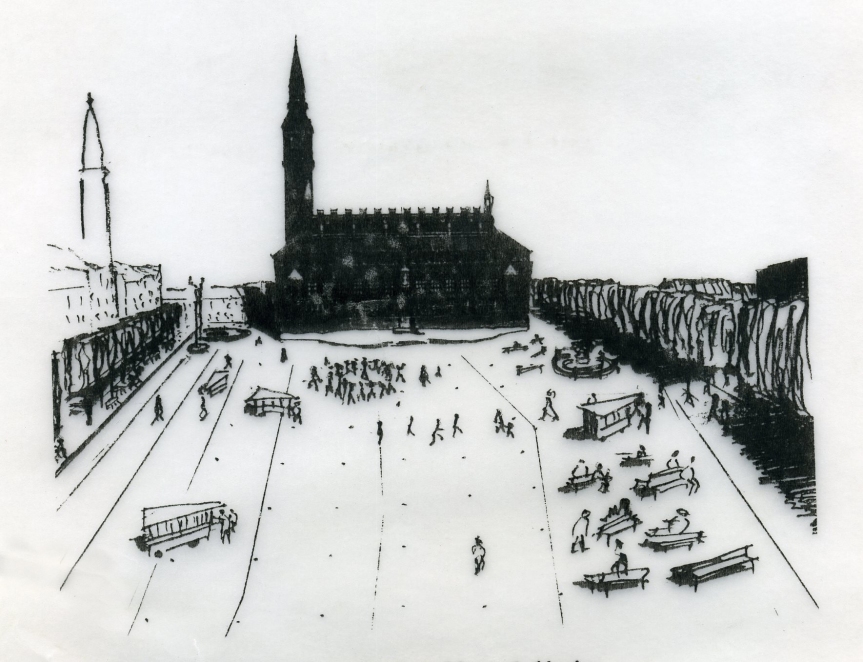

Politiken har med netop Rådhuspladsen selv leveret et godt eksempel på, at det ikke behøver at være sådan – at det ‘kreative monopol’ kan brydes ved at lade andre end arkitekter og byplanlæggere komme til orde. I 1997 da den nye busterminal havde afskåret Politikens Hus fra resten af pladsen, iværksatte avisen en artikelserie og en konkurrence for alle læsere med idéer om, hvordan pladsen kunne udformes. Konkurrencen blev formet på en måde, så alle kunne være med, bare man tegnede sine ideer ind på et præfabrikeret foto af Rådhuspladsen. Der indkom en stor mangfoldighed af projekter – fra van(d)vittige ideer hvor hele pladsen blev til et stort vandbassin, man kunne sejle rundt i, til mere realistiske ideer, med smukke belægninger og pæne tegninger. Det var især den sidste type, der blev præmieret, herunder mit eget projekt, der modtog en 2. præmie. Ud over lidt medieomtale skete der desværre ikke mere.

Konkurrencen er et eksempel på en mere urban måde at skabe en unik ny Rådhusplads på. Man kunne også samle de bedste unge arkitekter, sociologer, kunstnere, iværksættere osv. fra hele verden og lade dem gå helt tæt på den lokale virkelighed. Ved at arrangere workshop, hvor borgere og byens øvrige parter deltager, kan der skabes et udfordrende møde mellem det lokale og det globale. Pointen er, at alle parter skal udfordres, og at det sker i et møde, hvor alle stilles lige. De uforudsigelige urbane mutationer og den dynamik, der skabes ved at lade tilblivelsen af den mest centrale plads i byen foregå i det ‘offentlige rum’, vil sætte København på det internationale landkort.

København kunne profilere sig som en åben by, der virkelig appellerer til et væld af forskellige mennesker ved at gøre byboerne til medskabere af deres by. Det er på tide, vi dyrker det simple faktum, at vi lever mange sammen, og at vi udnytter det potentiale, der ligger gemt i at skabe udfordrende og konstruktive møder mellem byboerne.

En urban metropol.

Jens Brandt, arkitekt MAA og urbanist. Medstifter af byudviklingslaboratoriet Supertanker. Senest har Supertankeren udsendt sin ‘Urban Task Force’ i Københavns Sydhavn

Urbanitet

Urbaniteten handler dybest set om, hvad der kan ske, når en mangfoldighed af mennesker lever på samme sted under konstant forandring. En væsentlig side af det urbane består i en åben og respektfuld ‘urban’ måde at omgås hinanden på. Byens liv og evne til at forny sig er afhængig af de nye og uventede ideer, netværk, osv. der opstår i det urbane møde mellem forskellige mennesker.

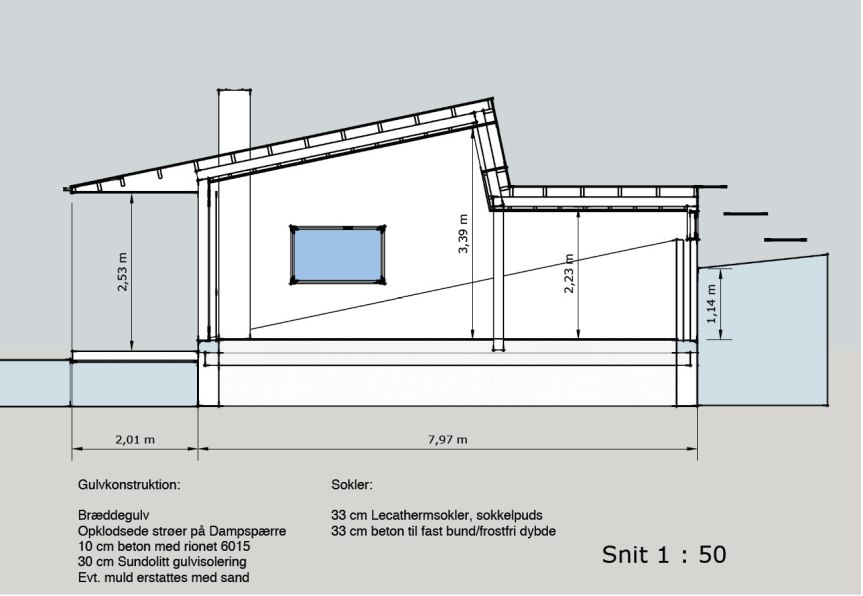

Plan RH: Den overordnede idé er at understrege overgangen mellem den gamle ”langsomme” by til den nye og dynamiske by. En samling af pladsen sker ved at nedlægge Vester Voldgade og lægge H.C. Andersens Boulevard ned i en tunnel. Mod den gamle by på solsiden er der lagt op til nydelse med et rigt caféliv og en badstue under et rundt vandspejl. Mod den nye by fungerer overdækningen af H.. Andersens boulevard som busterminal for at understrege byens mobilitet og dynamik.

H. C. Andersens Boulevard med ny busterminal ovenpå den gennemkørende trafik. Overdækningen sikrer en kobling mellem Strøget og Vesterbrogade og udvider således City.

Lurblæserne: Denne plads er en overset perle med masser af sol. Her skabes der en intim plads, hvor kroppens dimension understreges af en badstue under et cirkulært vandspejl.

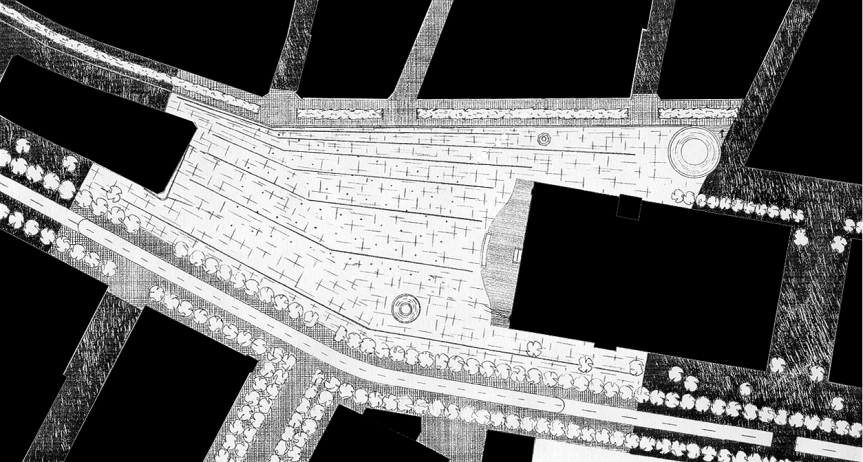

RH set fra oven: Dette var den ”obligatoriske tegning som alle, der deltog i Politikens konkurrence som et minimum skulle tegne. Pladsens motto er ”alting på hjul” så brugen af pladsen hele tiden kan ændres og f.eks. kan pølsevogne og byinventar hurtigt ryddes af vejen til den store fest.